A Transatlantic Perspective on the Cybersecurity Industry: Observations From Both Sides

"The US is the best at business and war." I did war and now I do business.

"It's good to learn from your mistakes. It's better to learn from other people's mistakes.” — Warren Buffett (or Eleanor Roosevelt, or Abraham Lincoln, or…)

I worked in national defense & intelligence for the US government half my ~20yr career, then did product management and team leadership for enterprise cybersecurity in the second half.

But then I moved to Europe.

I joined a Dutch-native cybersecurity scale-up earnestly aspiring to compete with leaders in an industry dominated by well-capitalized American companies1.

The first thing I’m asked professionally when meeting someone in my industry here after revealing my American career is almost always, "What are some industry differences between the US and Europe?"

There are key differences in operational and strategic approaches to business, as well as personnel and the talent pipeline. Because of these differences, both markets have much to learn from each other and should continue working together to build diverse workforces where international resources are available.

I'll share some impressions on working in cybersecurity in EU vs US here. It's only a start as there are a dozen interesting relevant topics possible in this space. It's also only my opinion and many may differ — even me!

Strategic vs Tactical: US & EU Scopes-of-Thought

The European Union is 27 Member States with 24 official languages and is a supranational entity more resembling a confederation than federation, with some familiar characteristics to both forms. There is a common foreign affairs representative, executive, and security policy2; however, these entities don't represent a "United States of Europe" or share the federalized institutional culture of the United States. As such, each state retains domestic interests and policies in their own national interests. The extent of Hobbesian firmness slides along a scale (probably) most strongly correlated with each country's energy interests, followed by winds of domestic political power.

Across the ocean, the US has a post-WW2 history of global engagement beyond European military interests — although they are common partners. The US considers its reach so vast that it divides the world into military combatant commands, with periodic modernizations and updates for (global) functional and regional commands (Figure 1). The European Union Member States thus far remain primarily focused on near affairs and Allied engagements where European military expenditure as percentage of GDP is comparatively limited. In other words, sometimes for better and sometimes for worse, the US wraps its arms around the globe while Europe strengthens its grip on itself3.

This mindset, I'd argue, reverberates throughout both business and policy cultures and latently affects security leaders’ scope of thinking.

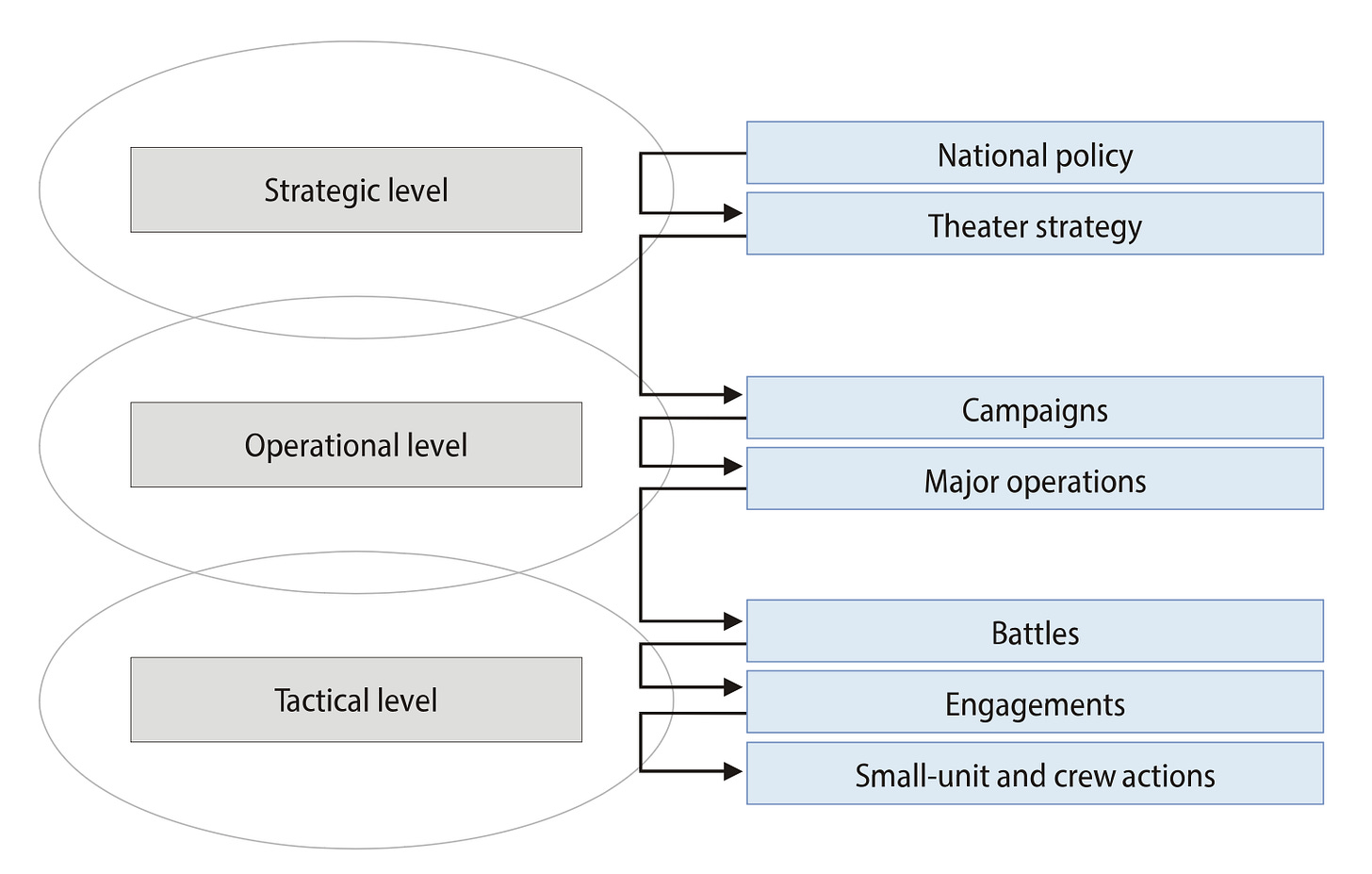

That correlation is admittedly speculative on my part as a former military planner, but the general gist of the difference in thinking aligns with my European and American peer observers. Therefore regardless of the true causes, it is my opinion European enterprise security leaders and cybersecurity vendors commonly — but not exclusively — operate in the operational and tactical levels of war (see Figure 2) as applied to a business context.

This means I’ve observed European security leaders are often concerned with issues typically associated with a Security Operations Center (SOC) and specifically technical characteristics, akin to “campaigns” and “battles,” and less with fully integrating intelligence and security operations into top-level strategic business operations (akin to “national policy”).4

A graphic applying this concept to cyber intelligence or security operations more broadly is above (Figure 3). You may add technical as a counterpart category to tactical in such context. This is because many SOC-specific operations deal with more fine-grained and higher-fidelity requirements than broader “tactical” issues, which can include threat hunting — which also may fit into operational contexts — and feeds used in varying contexts depending on the type and use case.

The next section works within the upper left quadrant.

Enterprise Strategy & Requirements

The most highly-developed organizations incorporate intelligence requirements aligned with strategic business priorities into their cybersecurity programs. Intelligence requirements processes have been written about extensively elsewhere. Ultimately this means instead of collecting data or information to process into intelligence — a tool to enable decisions across the “levels of war” — based on arbitrary measures or what a vendor provides, these organizations prioritize what matters most to them first and synthesize intelligence based on those priorities. These priorities involve either collection priorities, production (internal business) priorities, or both.

This is crucial because:

It minimizes resource exhaustion or mismanagement (intelligence production, procured feeds, personnel hours, etc.).

It minimizes blind spots. Given a scenario in which a threat targets a large financial institution responsible for underwriting the majority of national mortgage originations, for example, software and integrations enabling those transactions with third parties may live behind obscure infrastructure not otherwise considered a top target by a cybersecurity team.

It empowers security leadership to demonstrate value and return to the Board or national leadership by tying security efforts directly to business priorities, including successes.

It allows for a true risk mitigation program based on organizational assets, crown jewels, and stakes rather than media headlines or threats that may not apply to organizational or business continuity needs.

It necessitates communication between security teams and cross-functional executive leadership, easing channels ahead of or during serious security incidents and granting access to the information required to build a proactive program.

To #2, I can relay an anecdote in which I spoke with an executive in charge of financial payments processing worth trillions of US dollars annually. I sought to inform intelligence requirements and priorities to better safeguard the organization against compromise and financial loss. The business head had no insight into cybersecurity matters, but was keenly aware of the consequences of all-cause wire fraud, sabotage, or service disruption. It’s a security leader’s job to translate those interests into cybersecurity priorities. This dialogue is absent at lower levels of “war” without the first working within the higher levels to cascade planning down-echelon.

Incorporating requirements planning into standard operating procedure is becoming more common in European organizations, but remains comparatively elusive as a component of strategic security planning. Leading US enterprises have done this for the better part of a decade, spear-headed by financial institutions and evangelized to a higher level through risk registry program development by special organizations such as the Analysis & Resilience Center.

European organizations remain commonly focused on solving technical, reactive problems; and must change. Much has also been written about building a SOC, a critical first component in a cybersecurity program, but the strategic layer is too often absent in European enterprise.

Vendor Reflections

In part as a response to the above enterprise scenario and in part because of what I will discuss in the next section regarding IT pipelines, cybersecurity vendors based in Europe tend to focus on technical problems and prioritize security operations centers. This difference is therefore reflected in vendor space as well.

Quantitative market analysis and data sets can be found elsewhere, ranging from the previously linked blog to traditional analyst outlets such as Gartner and MarketsandMarkets; and many cybersecurity companies are publicly listed. That is for another blog. These impressions are based on experience and are qualitative. To that end, native European cybersecurity companies aspiring to growth commonly focus on:

Threat hunting (operational, tactical)

Security Operations Center solutions for detect & block

Business-to-consumer solutions, e.g. mobile device monitoring or antivirus

Standardized data aggregation solutions for processing SOC data

Niche toolsets such as malware sandboxes and highly-specialized analysis software

Small red team consulting services

In contrast, the leading global cybersecurity companies are US-based and are often:

Increasingly horizontally-integrated across product segments or consolidated platforms

Robust, rapid-release Software-as-a-Service products

Packaged with strategic intelligence or expert analytic content to empower decisions based on the information provided by the platform

Marketable directly into the Office of the Chief Information Security Officer and security leadership (security ratings services, cyber risk management or quantification tools, fully-integrated product suites, etc.)

Some of these traits are attributable to disparities in capital investment and market sizing, but I’d argue they are also to some extent a product of contrasting mindsets and priorities.

Europe: A More Technical Talent Pipeline

I was part of the US Cyber Command Establishment Team in 2008-09. Workforce development and assignment, while not an explicit part of my remit, was top of mind during this time. (This was also true for all organizations adopting “cyber” and cyber warfare concepts through at least 2014 in Pentagon circles).

We asked ourselves a key question many organizations still ask today:

Is it better to to hire technical personnel and train them in intelligence, or hire intelligence personnel and train them in technical issues?

The truth was there was no clear answer and the later NIST’s NICE Framework attempted to better document different knowledge, skills, and abilities required for personnel across roles. US Cyber Command consisted of Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), National Security Agency (NSA), and military personnel.

DIA and other all-source national intelligence agency personnel came with intelligence analytic expertise, but seldom were technically adept the in same way as NSA counterparts. Tech people know how to think analytically, but lack training in recognizing cognitive biases and strategic analysis. Intelligence people know how to recognize cognitive biases and write for intelligence, but lack expertise in TCP/IP, malware analysis, etc. NSA personnel often came from a technical pedigree: hacking/cracking, coding, reversing. DIA personnel came from an intelligence pedigree: political science, international affairs, humanities.

In cybersecurity, Europeans come from an IT pedigree. Americans come from a mixture, but more commonly possess a humanities or political background than do Europeans.

The European employment pipeline has leading technical schools; and cybersecurity attracts technical experts in the region. Many Europeans come from security operations centers, or from software and underground technical communities. Therefore, they think in tactical terms and serve themselves well in the aforementioned red teaming, threat hunting functions. They think analytically, but lack training in recognizing cognitive biases or making strategic recommendations to business leadership.

The North American pipeline consists of more national security personnel and intelligence personnel. This makes sense, as the Pentagon is one of the world’s largest employers and there are roughly 1.3 million people with a Top Secret security clearance in the US. Combine this with the earlier observations about the mindset I argue is programmed into the culture and the division starts to make sense.

Integrating Mindsets

These differences are not universal. For each example given, I know I have contacts to counter them in both regions. Nor are both regions monolithic. The further south and east one travels on the Continent, the smaller budgets tend to be (though this too can change — particularly with recent events). There are differences across industry verticals, differences across governments, and differences that apply across regions but are the same in counterpart verticals transatlantically. I can’t address everything with universal truth; only my experiences.

The broader takeaway is to adopt the best ideas of each approach. We need technical specialists and we need a strong security operations mind and program build in every organization responsible for critical information assets. We also need strategic vision and a thorough understanding of risk mitigation in accordance with business or national priorities. We need experts with training in cognition, humanities, and analytical writing; just as we need experts who can reverse engineer malware. As with security and trade, they just need to work together and serve the same end.

Future Topics

This article captures only a portion of possible topics on this issue and many are open for deeper digging.

In a future post I may address…

EU CISO As IT Leader ➡ CISO As Business Leader

Comparative Enterprise Budgets

A World Where Open Source (Kind Of) Won: Europe’s gravitation toward open source solutions

Regulatory and compliance contrasts: Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification, NIST Five Functions, EU Network and Information Security (NIS) Directive, etc.

National Cyber Security Centers (NCSCs) across EU 27 vs. US approach

Differences in threat landscape priorities: Europe’s bigger state infrastructure

Deeper digging beyond intelligence requirements into cyber risk, etc., as the discussion here was limited (there is great material on this already however and I prefer to focus on EU/US learnings)

Suggestions or preferences welcome.

Post-Script: Elephant In The Room

This article is primarily focused on industry and organizational differences, but I’d like to address the most common concern I encounter: effects on day-to-day life; i.e. money. Skip this section if it isn’t interesting to you. I find it’s typically what most Americans really want to know first as they are often considering relocating to Europe, whereas the organizational and practical differences is what Europeans want to know first.

There are countless studies and threads regarding “Europe vs. America” tech salaries5. As an American living abroad I’ve collected a handful of key distilled points and provide my conclusions here. I hold perspective as a senior-level corporate employee as well as a hiring official. Perspectives on founders and entrepreneurship, beyond navigating business strategy at a scale-up, carry significant capital investment and networking implications better-suited for another article.

Per the footnote above referencing available discussions on this topic, salaries between US and EU are controversial. General tech salaries may not apply to cybersecurity industry, but the broad sentiment in such threads applies in my hiring experience: the US is simply much, much higher. A good mid-level analyst or CTI manager may expect $190-250K USD TC in the US and can expect one-third to half that in EU. An executive or VP can add $100-200K in the US, depending on role and experience, but will seldom see even what a mid-level worker with 1/3rd the experience earns in the US.

The difference is attributable to dozens of factors, but it can affect hiring from the US and candidates will ask numerous questions about the trade-off.

In my experience the differences in health care expenses, child care, and retirement plans don’t come close to making up for the difference in cybersecurity industry. High-skilled industry workers simply sacrifice wealth in Europe vs in the US in most cases.

Most cybersecurity professionals in the US have access to a strong health care plan, rendering typical fears about US medical bankruptcy irrelevant (although you will never stop hearing about it).

Child care in countries like The Netherlands still costs 1800-2200 EUR/mo per child since most in cybersecurity are considerably above the means-tested eligibility cut-off for significant subsidies (it’s better in some other countries and the government wants to address the problem).

Most Western European countries are adopting or have adopted similar “save your own way or receive very little” retirement systems as the US. The Netherlands, like many European countries, has a three-pillar pension system. This system is excellent as most, but not all, Dutch employers contribute to your retirement on top of state and personal contributions — but it is best for life-long contributors and carries special tax challenges for US citizens, per the section below.

Many find the quality of life, however, and particularly the urbanism superior; and experience in Europe can be a strong career asset. European companies also have lower-friction access to markets with linguistic differences US salespersons can struggle with. Exposure to this >$20 trillion market and European business practices provides invaluable knowledge and experience.

It’s crucial to calculate this equation beyond financial considerations alone and I encourage people from the US to think through their personal circumstances and values. The wider array of factors is complex and dependent on the individual. No place is best for everyone and such preferences are exclusively personal.

Special For US Citizens: Lifelong Global Tax Requirements

A final note: America is one of two nations in the world to tax its citizens based on their citizenship, not residency (the other nation is Eritrea). This means all income must be reported to the US Internal Revenue Service for the rest of your life as an American citizen or Green Card holder, regardless of where you live; work; or whether you have ever been to the US. As the tax system is based on your passport and not your residency, this applies regardless of whether your income is related to the US. In fact, income earned abroad — even wages earned in your permanent home abroad with a permanent local employer — is considered “foreign income” and is taxed by the US for life.

While there are exclusions up to a certain income limit — for income earned from wages (the alternative is a tax crediting election) — and many countries have treaties for retirees to prevent complications in collecting state pensions, these benefit primarily either lower-income elderly less likely to move abroad or early/mid-career earners with limited long-term financial planning interests. They don’t address problems with different pension contribution systems (seen as “foreign” regular income), limitations in investment options, and numerous other issues.

The unusual US citizenship-based tax policy also introduces extraordinary challenges for founders abroad because of convoluted filing complications and other taxes levied on US citizen business owners within foreign (non-US) jurisdictions.

Incidentally, while this policy makes financial life difficult for US citizens abroad, it is unlikely to generate much income for the US Treasury since most filers don’t owe any tax after exemptions. The tax burden largely sits with those likeliest to read this article: senior level or experienced highly-skilled workers, entrepreneurs, and planners. But all US citizens abroad must file as well as report their local (“foreign”) banking activities or face enormous fees, often for filing mistakes or ignorance of the law, for the remainder of their lives6.

The policy primarily indirectly generates revenue for tax prep & tax tech firms, which lobby against change as Americans living abroad use their services to fulfill increasingly complex requirements.

As all tax discourse is politically charged, I’ll direct readers to this page for more information. In the meantime, it’s an important component for globally-mobile Americans interested in financial planning beyond short-term employment wage income to track closely with an accounting firm.

Richard Stiennon’s research is the best curated source of industry & vendor data I have seen. Exploring Crunchbase data also reveals a heavy revenue and capital bias toward the United States in cybersecurity with very few European companies, a) remaining European-owned; b) receiving large capital injections relative to US competitors, or c) remaining headquartered in Europe.

The security policies of the European Union and disparate relevant organizations are complex and beyond the scope of this article (or probably any article not also a doctoral dissertation).

2022-23 developments in the Russo-Ukrainian War may affect this dynamic, but thus far its implications for European involvement beyond the continent seem concretely limited in the medium term apart from notable strategic agreements regarding semiconductor intellectual property.

Please note this is by no means universal. This is particularly changing in large financial institutions and central governments across Europe. The Nordics often lead the way here.

I suggest perusing any of Hacker News/Y Combinator’s periodic threads here. You’ll be occupied for hours, or until mental and emotional exhaustion.

The exception is through renunciation of citizenship. Americans abroad should be the best ambassadors for America, but regrettably America’s tax policy levied against its citizens permanently residing overseas has led to soaring renunciation rates. This is not among my personal moral considerations as a service-oriented national security veteran who may return to the United States — however, it is unfortunately a common discussion point for Americans living overseas.